So I have been using the internet for research since I was 11, which is decades and decades, and there aren’t very many websites up now that are even half that old.

What I wanted to share with you today was some websites that I’ve been using for a really long time, that have held up and been useful the whole time, and that recently sent me back down an old rabbit hole in a new way.

So, one of my long-term ongoing projects that I have chipped away at in fits and starts since high school has been Orin and the Dead Man’s Sword, and one of the pillars of that for me has been wilderness-as-character. I started off as a teen by looking at how European fantasy has taken the European wilderness and created a kind of hyperreal version of it; I wanted to see how I could do something similar to the wilderness around me here in southern Ontario, Canada.1

So one of the things that I have been researching more intentionally since undergrad has been the canadian wilderness, and one of the things I have been mulling over more and more has been how to explore and kind of personify it in my fiction, in ways that don’t feel like I am stepping on indigenous practices and languages and belief systems.2

The place that I decided to start was a straightforward ecological understanding of what is here currently. At the time, say, 2008/2009, mostly I just sort of googled things, like, “what birds do we have in Ontario” etc. And once I got tired of learning about animals, I realized I was going to have to learn about plants, and that’s when I discovered this group of websites that ended up being such a big part of my research and my sketchbook practice a little over a decade ago.

These websites are Ontario Trees & Shrubs, Ontario Ferns, Ontario Wildflowers and Ontario Grasses. They’re wonderful references, listing plants by common or latin names, by families, by things like flower colours or numbers of petals, by habitat or fruiting season, all done in a painstaking and straightforward web 1.0-feeling way. Each listing has a selection of photographs to help with identification in various seasons and states of growth. Each website also connects you to a few scientific in jokes, related philosophical writing, and more.

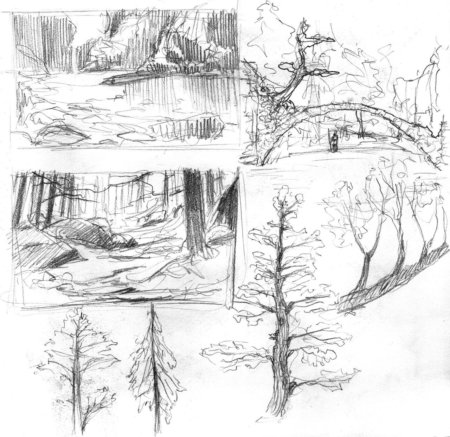

I used these aggressively to build out landscapes in my Orin comic, and my sketchbooks are full of studies where I worked hard to cartoon and simplify the distinctive shapes of black spruce branches, red cedar trunks, and more. They’re all extremely helpful, useful and straightforward, and honestly if they were ebooks I could purchase to keep offline on my phone while I hike, I would pay good money towards that!

But that’s not what we’re talking about here today, despite the impressive work done here and the longevity of the websites and their use.

There is a fifth website that is part of this network, a beautiful website that isn’t really Ontario specific, but that recently opened up a whole world for me that I hadn’t paid any attention to before, called World of Mosses.

The four reference websites of Ontario flora are run by Walter Muma, and World of Mosses is also run by Walter, but as a tribute to the work of his late father Robert Muma, who was deeply passionate about moss and produced an enormous amount of research and writing and art on the subject.

World of Mosses is a really beautiful web 1.0 experience, taking you through information in a linear way but also letting you zip between pages if relevant. It doesn’t feel quite as specifically purpose-built as the four reference sites, intermixing texts about moss morphology with beautiful artwork. For a website that’s been online since 20043 it doesn’t feel awkward or uncomfortable to use at all, though I will admit the image sizes feel tragically small now on our modern internet and monitors.

Sadly, the shop aspect of the website is no longer running, so you can’t buy yourself a moss card or book any longer, but you can still look at the art AND read through the book as webpages, which I really appreciate.

This came back into my radar after I started trying out macro photography and realized I have almost no understanding of what mosses are, how they grow, why they seem to .. bloom? sometimes? and more. I found myself coming back to this website to try and see if I could use it to identify some of my photographs, and see what else I can learn about moss to keep in mind as I go out and shoot more in future.

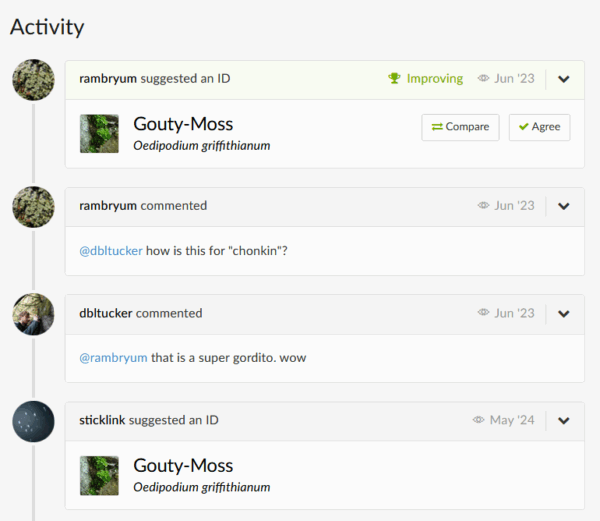

Moss identification has turned out to be enormously complicated compared to tree or flower identification, at least as a complete ecology amateur. The World of Mosses website does not attempt to identify every single moss species, and it doesn’t replace something like crowdsourced photo id apps like iNaturalist or Seek.4 It is however an incredible introduction into mosses as a whole category of living things, giving you an introductory understanding of their life cycle and their needs, and all of it is absolutely suffused with the joys of learning about them. And yes, you will be able to identify some mosses after reading this website, it just turns out that there’s so, so many of them out there that you can only really touch the tip of the taxonomic iceberg.

I really enjoy photographing moss. It’s really one of the most beautiful plants out there, I think, and macro-photographing it has the added layer of revealing something to me that I didn’t know I didn’t know – what moss is composed of, what it actually is. I think a lot of people out there don’t really know what it looks like, since it is so very small.

So firstly, I hope this post inspires you to go look at some moss! But because I am the way I am, it also made me think a lot about the personal internet, archives, legacy, etc.

Coming back to this website now, while I’ve been revitalizing my own blog and thinking about my own archive, has me wondering a lot more about Robert Muma, who had been gone for over a decade when the World of Mosses website first appeared on the internet5 in 2004. Thankfully, Walter also runs a more general archive of Robert Muma’s work, at Mumart.

Robert Muma was a Toronto area craftsman6; he worked in bookbinding and leathercraft and scientific illustration. After rediscovering mosses in his retirement, his love of moss extended to an enormous collection of carefully prepared samples7 and many beautiful scientific illustrations done from stereo microscope imagery; you can see in his book on mosses the way he combines that scientific layer with a beautiful combination of illustration and calligraphy.

Side note: Walter specifies throughout all his sites that reposting the imagery is not allowed without explicit permission, which does feel a bit awkward to me on today’s chaotic internet. I will admit that was skeptical about this for a minute – I would really like to share all this beautiful art with you, and I know you’re more likely to actually look at it if I repost, link and give attribution. But hey, there’s an explicit ask, and I respect that, even if it seemed a bit eccentric to me. So please actually do go click over and look at Robert’s work; it’s well worth your time!8

Having this website as an archive and tribute to Robert Muma’s work on mosses has meant that now, two decades after it was published and more than three decades since he passed, his hard work continues to inspire and connect people to his beloved subject. That’s amazing. That’s really beautiful!

A couple more recent mentions, just to show you how his work continues to ripple out into the world:

…and fun fact, the artist of Moss Notes has continued making her own moss art as part of her scientific practice over on instagram!

What a gift from Walter to his father, archiving his work online in this way! Keeping that website up has made this work on mosses available to behave as exactly what it seems intended to have been – an inspiring springboard to help the curious casual observer fall in love with mosses, and start to understand their magic and mystery and weirdness alongside a passionate observer.

Makes you think that the internet might be alright, actually.

Also, if you want to peruse more images of moss, and maybe even try your hand at painting some yourself, I super recommend browsing the observations on iNaturalist:

If you change the search filter CC choice to CC0, then you will only see copyright free imagery that you can safely work from with no legal complications. And sorting by “favs” instead of posting date will turn up some real treasures as well!

It’s a delightful community on there, too – the moss folks seem both passionate and chill so far:

Go forth and have fun and get pumped on moss and also maybe write a blog post about something you love, while you’re at it!

- my teenage conception of canadian wilderness as free of cultural meaning to anyone was hilariously uninformed, and shoutout to the indigenous artists who shared so much with me and my classmates in undergrad at art school and helped me stop shoving my foot in my mouth on that one. ↩︎

- this quest continues. ↩︎

- according to the internet archive, at least. ↩︎

- though to be honest those are really struggling with mosses too in my experience! ↩︎

- …again, according to my research on the internet archive, which, well, best I could do. ↩︎

- Toronto local sighting! ↩︎

- since donated to the Royal Ontario Museum, where you can peruse them in the ROM’s digital collections: https://collections.rom.on.ca/advancedsearch/objects/creditline%3ARobert Muma/images?page=1 ↩︎

- this is why this post is illustrated entirely with my own moss photos, awkward as they are. ↩︎

Leave a Reply